Memory Management

Memory Allocation on Heap

Allocator Initialization

When using programming languages, dynamic memory allocation is often encountered, such as allocating a block of memory through malloc or new in C, or Vec, String, etc. in Rust, which are allocated on the heap.

To allocate memory on the heap, we need to do the following:

- Provide a large block of memory space during initialization

- Provide interfaces for allocation and release

- Manage free blocks

In short, we need to allocate a large space and set up an allocator to manage this space, and tell Rust that we now have an allocator, asking it to use it, allowing us to use variables like Vec, String that allocate memory on the heap. This is what the following lines do.

use buddy_system_allocator::LockedHeap;

use crate::consts::HV_HEAP_SIZE;

#[cfg_attr(not(test), global_allocator)]

static HEAP_ALLOCATOR: LockedHeap<32> = LockedHeap::<32>::new();

/// Initialize the global heap allocator.

pub fn init() {

const MACHINE_ALIGN: usize = core::mem::size_of::<usize>();

const HEAP_BLOCK: usize = HV_HEAP_SIZE / MACHINE_ALIGN;

static mut HEAP: [usize; HEAP_BLOCK] = [0; HEAP_BLOCK];

let heap_start = unsafe { HEAP.as_ptr() as usize };

unsafe {

HEAP_ALLOCATOR

.lock()

.init(heap_start, HEAP_BLOCK * MACHINE_ALIGN);

}

info!(

"Heap allocator initialization finished: {:#x?}",

heap_start..heap_start + HV_HEAP_SIZE

);

}

#[cfg_attr(not(test), global_allocator)] is a conditional compilation attribute, which sets the HEAP_ALLOCATOR defined in the next line as Rust's global memory allocator when not in a test environment. Now Rust knows we can do dynamic allocation.

HEAP_ALLOCATOR.lock().init(heap_start, HEAP_BLOCK * MACHINE_ALIGN) hands over the large space we applied for to the allocator for management.

Testing

pub fn test() {

use alloc::boxed::Box;

use alloc::vec::Vec;

extern "C" {

fn sbss();

fn ebss();

}

let bss_range = sbss as usize..ebss as usize;

let a = Box::new(5);

assert_eq!(*a, 5);

assert!(bss_range.contains(&(a.as_ref() as *const _ as usize)));

drop(a);

let mut v: Vec<usize> = Vec::new();

for i in 0..500 {

v.push(i);

}

for (i, val) in v.iter().take(500).enumerate() {

assert_eq!(*val, i);

}

assert!(bss_range.contains(&(v.as_ptr() as usize)));

drop(v);

info!("heap_test passed!");

}

In this test, Box and Vec are used to verify the memory we allocated, whether it is in the bss segment.

The large block of memory we just handed over to the allocator is an uninitialized global variable, which will be placed in the bss segment. We only need to test whether the address of the variable we obtained is within this range.

Memory Management Knowledge for Armv8

Addressing

The address bus is by default 48 bits, while the addressing request issued is 64 bits, so the virtual address can be divided into two spaces based on the high 16 bits:

- High 16 bits are 1: Kernel space

- High 16 bits are 0: User space

From the perspective of guestVM, when converting a virtual address to a physical address, the CPU will select the TTBR register based on the value of the 63rd bit of the virtual address. TTBR registers store the base address of the first-level page table. If it is user space, select TTBR0; if it is kernel space, select TTBR1.

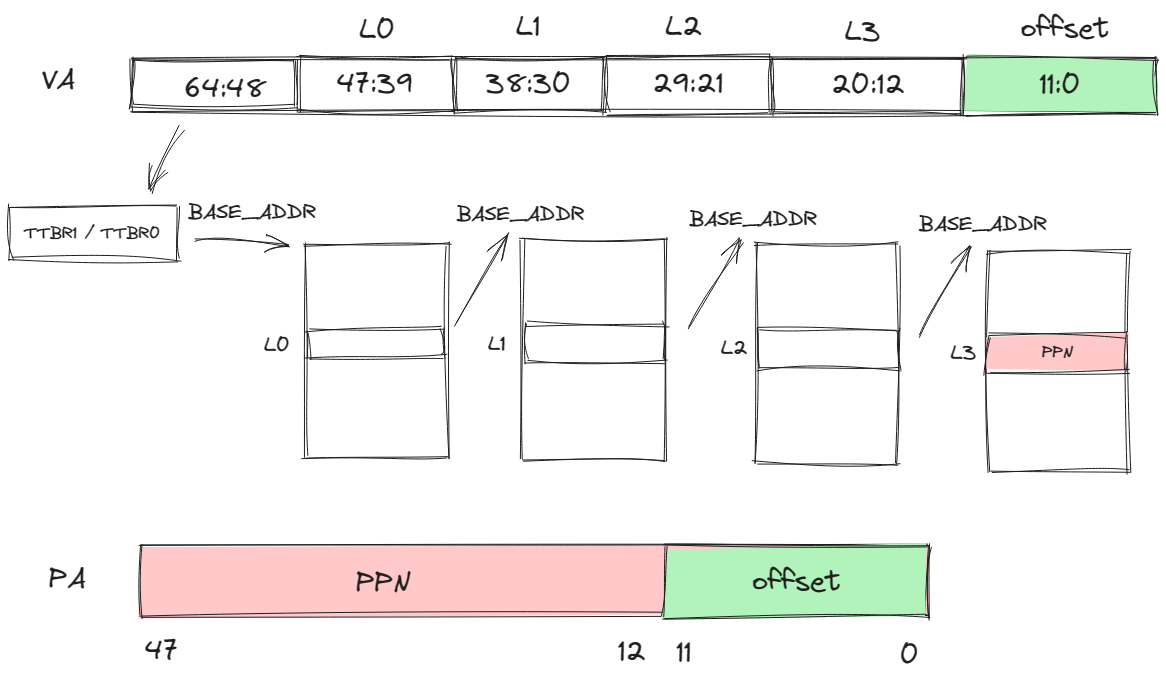

Four-Level Page Table Mapping (using a page size of 4K as an example)

In addition to the high 16 bits used to determine which page table base address register to use, the following 36 bits are used as indexes for each level of the page table, with the lower 12 bits as the page offset, as shown in the diagram below.

Stage-2 Page Table Mechanism

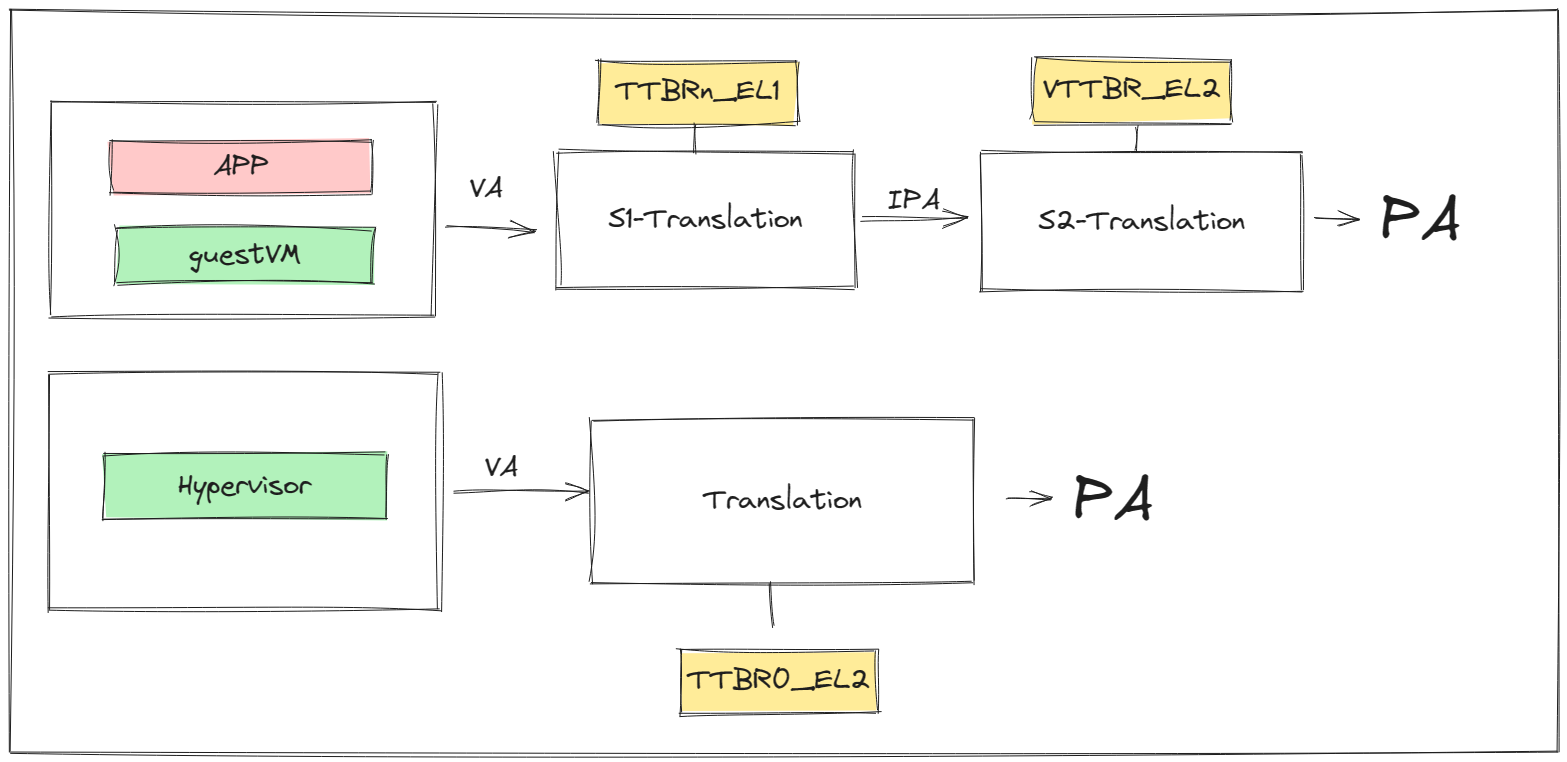

In a virtualized environment, there are two types of address mapping processes in the system:

- guestVM uses Stage-1 address conversion, using

TTBR0_EL1orTTBR1_EL1, to convert the accessed VA to IPA, then through Stage-2 address conversion, usingVTTBR0_EL2to convert IPA to PA. - Hypervisor may run its own applications, and the VA to PA conversion for these applications only requires one conversion, using the

TTBR0_EL2register.

Memory Management in hvsior

Management of Physical Page Frames

Similar to the heap construction mentioned above, page frame allocation also requires an allocator, then we hand over a block of memory we use for allocation to the allocator for management.

Bitmap-based Allocator

use bitmap_allocator::BitAlloc;

type FrameAlloc = bitmap_allocator::BitAlloc1M;

struct FrameAllocator {

base: PhysAddr,

inner: FrameAlloc,

}

BitAlloc1M is a bitmap-based allocator, which manages page numbers, providing information on which pages are free and which are occupied.

Then, the bitmap allocator and the starting address used for page frame allocation are encapsulated into a page frame allocator.

So we see the initialization function as follows:

fn init(&mut self, base: PhysAddr, size: usize) {

self.base = align_up(base);

let page_count = align_up(size) / PAGE_SIZE;

self.inner.insert(0..page_count);

}

The starting address of the page frame allocation area and the size of the available space are passed in, the number of page frames available for allocation in this space page_size is calculated, and then all page frame numbers are told to the bitmap allocator through the insert function.

Structure of Page Frames

pub struct Frame {

start_paddr: PhysAddr,

frame_count: usize,

}

The structure of the page frame includes the starting address of this page frame and the number of page frames corresponding to this frame instance, which may be 0, 1, or more than 1.

Why are there cases where the number of page frames is 0?

When hvisor wants to access the contents of the page frame through

Frame, it needs a temporary instance that does not involve page frame allocation and page frame recycling, so 0 is used as a flag.

Why are there cases where the number of page frames is greater than 1?

In some cases, we are required to allocate continuous memory, and the size exceeds one page, which means allocating multiple continuous page frames.

Allocation alloc

Now we know that the page frame allocator can allocate a number of a free page frame, turning the number into a Frame instance completes the allocation of the page frame, as shown below for a single page frame allocation:

impl FrameAllocator {

fn init(&mut self, base: PhysAddr, size: usize) {

self.base = align_up(base);

let page_count = align_up(size) / PAGE_SIZE;

self.inner.insert(0..page_count);

}

}

impl Frame {

/// Allocate one physical frame.

pub fn new() -> HvResult<Self> {

unsafe {

FRAME_ALLOCATOR

.lock()

.alloc()

.map(|start_paddr| Self {

start_paddr,

frame_count: 1,

})

.ok_or(hv_err!(ENOMEM))

}

}

}

As you can see, the frame allocator helps us allocate a page frame and returns the starting physical address, then creates a Frame instance.

Recycling of Page Frames

The Frame structure is linked to the actual physical page, following the RAII design standard, so when a Frame leaves the scope, the corresponding memory area also needs to be returned to hvisor. This requires us to implement the drop method in the Drop Trait, as follows:

impl Drop for Frame {

fn drop(&mut self) {

unsafe {

match self.frame_count {

0 => {} // Do not deallocate when use Frame::from_paddr()

1 => FRAME_ALLOCATOR.lock().dealloc(self.start_paddr),

_ => FRAME_ALLOCATOR

.lock()

.dealloc_contiguous(self.start_paddr, self.frame_count),

}

}

}

}

impl FrameAllocator{

unsafe fn dealloc(&mut self, target: PhysAddr) {

trace!("Deallocate frame: {:x}", target);

self.inner.dealloc((target - self.base) / PAGE_SIZE)

}

}

In drop, you can see that page frames with a frame count of 0 do not need to release the corresponding physical pages, and those with a frame count greater than 1 indicate that they are continuously allocated page frames, requiring the recycling of more than one physical page.

Data Structures Related to Page Tables

With the knowledge of Armv8 memory management mentioned above, we know that the process of building page tables is divided into two parts: the page table used by hvisor itself and the Stage-2 conversion page table. We will focus on the Stage-2 page table.

Before that, we need to understand a few data structures that will be used.

Logical Segment MemoryRegion

Description of the logical segment, including starting address, size, permission flags, and mapping method.

pub struct MemoryRegion<VA> {

pub start: VA,

pub size: usize,

pub flags: MemFlags,

pub mapper: Mapper,

}

Address Space MemorySet

Description of each process's address space, including a collection of logical segments and the corresponding page table for the process.

pub struct MemorySet<PT: GenericPageTable>

where

PT::VA: Ord,

{

regions: BTreeMap<PT::VA, MemoryRegion<PT::VA>>,

pt: PT,

}

4-Level Page Table Level4PageTableImmut

root is the page frame where the L0 page table is located.

pub struct Level4PageTableImmut<VA, PTE: GenericPTE> {

/// Root table frame.

root: Frame,

/// Phantom data.

_phantom: PhantomData<(VA, PTE)>,

}

Building the Stage-2 Page Table

We need to build a Stage-2 page table for each zone.

Areas to be Mapped by the Stage-2 Page Table:

- The memory area seen by guestVM

- The IPA of the device tree accessed by guestVM

- The memory area of the UART device seen by guestVM

Adding Mapping Relationships to the Address Space

/// Add a memory region to this set.

pub fn insert(&mut self, region: MemoryRegion<PT::VA>) -> HvResult {

assert!(is_aligned(region.start.into()));

assert!(is_aligned(region.size));

if region.size == 0 {

return Ok(());

}

if !self.test_free_area(®ion) {

warn!(

"MemoryRegion overlapped in MemorySet: {:#x?}\n{:#x?}",

region, self

);

return hv_result_err!(EINVAL);

}

self.pt.map(®ion)?;

self.regions.insert(region.start, region);

Ok(())

}

In addition to adding the mapping relationship between the virtual address and the logical segment to our Map structure, we also need to perform mapping in the page table, as follows:

fn map(&mut self, region: &MemoryRegion<VA>) -> HvResult {

assert!(

is_aligned(region.start.into()),

"region.start = {:#x?}",

region.start.into()

);

assert!(is_aligned(region.size), "region.size = {:#x?}", region.size);

trace!(

"create mapping in {}: {:#x?}",

core::any::type_name::<Self>(),

region

);

let _lock = self.clonee_lock.lock();

let mut vaddr = region.start.into();

let mut size = region.size;

while size > 0 {

let paddr = region.mapper.map_fn(vaddr);

let page_size = if PageSize::Size1G.is_aligned(vaddr)

&& PageSize::Size1G.is_aligned(paddr)

&& size >= PageSize::Size1G as usize

&& !region.flags.contains(MemFlags::NO_HUGEPAGES)

{

PageSize::Size1G

} else if PageSize::Size2M.is_aligned(vaddr)

&& PageSize::Size2M.is_aligned(paddr)

and size >= PageSize::Size2M as usize

&& !region.flags.contains(MemFlags::NO_HUGEPAGES)

{

PageSize::Size2M

} else {

PageSize::Size4K

};

let page = Page::new_aligned(vaddr.into(), page_size);

self.inner

.map_page(page, paddr, region.flags)

.map_err(|e: PagingError| {

error!(

"failed to map page: {:#x?}({:?}) -> {:#x?}, {:?}",

vaddr, page_size, paddr, e

);

e

})?;

vaddr += page_size as usize;

size -= page_size as usize;

}

Ok(())

}

Let's briefly interpret this function. For a logical segment MemoryRegion, we map it page by page until the entire logical segment size is covered.

The specific behavior is as follows:

Before mapping each page, we first determine the physical address paddr corresponding to this page according to the mapping method of the logical segment.

Then determine the page size page_size. We start by checking the 1G page size. If the physical address can be aligned, the remaining unmapped page size is greater than 1G, and large page mapping is not disabled, then 1G is chosen as the page size. Otherwise, check the 2M page size, and if none of these conditions are met, use the standard 4KB page size.

We now have the information needed to fill in the page table entry. We combine the page starting address and page size into a Page instance and perform mapping in the page table, which is modifying the page table entry:

fn map_page(

&mut self,

page: Page<VA>,

paddr: PhysAddr,

flags: MemFlags,

) -> PagingResult<&mut PTE> {

let entry: &mut PTE = self.get_entry_mut_or_create(page)?;

if !entry.is_unused() {

return Err(PagingError::AlreadyMapped);

}

entry.set_addr(page.size.align_down(paddr));

entry.set_flags(flags, page.size.is_huge());

Ok(entry)

}

This function briefly describes the following functionality: First, we obtain the PTE according to the VA, or more precisely, according to the page number VPN corresponding to this VA. We fill in the control bit information and the physical address (actually, it should be PPN) in the PTE. Specifically, you can see in the PageTableEntry's set_addr method that we did not fill in the entire physical address but only the content excluding the lower 12 bits, because our page table only cares about the mapping of page frame numbers.

Let's take a closer look at how to obtain the PTE:

fn get_entry_mut_or_create(&mut self, page: Page<VA>) -> PagingResult<&mut PTE> {

let vaddr: usize = page.vaddr.into();

let p4 = table_of_mut::<PTE>(self.inner.root_paddr());

let p4e = &mut p4[p4_index(vaddr)];

let p3 = next_table_mut_or_create(p4e, || self.alloc_intrm_table())?;

let p3e = &mut p3[p3_index(vaddr)];

if page.size == PageSize::Size1G {

return Ok(p3e);

}

let p2 = next_table_mut_or_create(p3e, || self.alloc_intrm_table())?;

let p2e = &mut p2[p2_index(vaddr)];

if page.size == PageSize::Size2M {

return Ok(p2e);

}

let p1 = next_table_mut_or_create(p2e, || self.alloc_intrm_table())?;

let p1e = &mut p1[p1_index(vaddr)];

Ok(p1e)

}

First, we find the starting address of the L0 page table, then obtain the corresponding page table entry p4e according to the L0 index in the VA. However, we cannot directly obtain the starting address of the next level page table from p4e, as the corresponding page table may not have been created yet. If it has not been created, we create a new page table (this process also requires page frame allocation), then return the starting address of the page table, and so forth, until we obtain the page table entry PTE corresponding to the L4 index in the L4 page table.

After mapping the memory (the same applies to UART devices) through the process described above, we also need to fill the L0 page table base address into the VTTBR_EL2 register. This process can be seen in the activate function of the Zone's MemorySet's Level4PageTable.

In a non-virtualized environment, why isn't guestVM allowed to access memory areas related to MMIO and GIC devices?

This is because, in a virtualized environment, hvisor is the manager of resources and cannot arbitrarily allow guestVM to access areas related to devices. In the previous exception handling, we mentioned access to MMIO/GIC, which actually results in falling into EL2 due to the lack of address mapping, and EL2 accesses the resources and returns the results. If mapping was performed in the page table, it would directly access the resources through the second-stage address conversion without passing through EL2's control.

Therefore, in our design, only MMIOs that are allowed to be accessed by the Zone are registered in the Zone, and when related exceptions occur, they are used to determine whether a certain MMIO resource is allowed to be accessed by the Zone.